“…here I dwell, where these sweet zephyrs move,

And little rivulets from the rocks add beauty to my grove.

I drink the wine my hills produce; On wholesome food I dine;

My little offspring ‘round me Are like clusters on the vine…”

Thomas Livezey, circa 1750

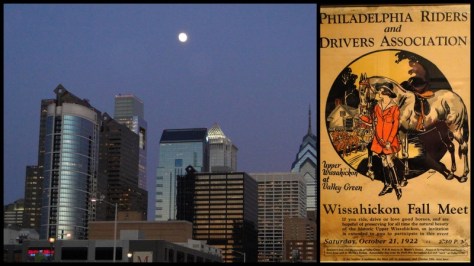

It’s Friday evening and we’re sitting on the great marble staircase having a drink and listening to jazz at the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Art After Five. Stepping out into the courtyard, the city at night glitters and hums like an urban engine. The following day, we leisurely stroll down Forbidden Drive in bucolic Valley Green after having lunch in an 1850 Inn. Mounted horses pass at full gallop and geese float down the Wissahickon Creek. We’re still within the city. Like all great urban centers, Philadelphia is a city of neighborhoods. Like all great cities, these neighborhoods evolve, and so it is with William Penn’s original square mile city of Philadelphia as well as leafy Chestnut Hill/Valley Green. The future doesn’t always preserve the past, and sometimes that’s good.

It’s Friday evening and we’re sitting on the great marble staircase having a drink and listening to jazz at the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Art After Five. Stepping out into the courtyard, the city at night glitters and hums like an urban engine. The following day, we leisurely stroll down Forbidden Drive in bucolic Valley Green after having lunch in an 1850 Inn. Mounted horses pass at full gallop and geese float down the Wissahickon Creek. We’re still within the city. Like all great urban centers, Philadelphia is a city of neighborhoods. Like all great cities, these neighborhoods evolve, and so it is with William Penn’s original square mile city of Philadelphia as well as leafy Chestnut Hill/Valley Green. The future doesn’t always preserve the past, and sometimes that’s good.

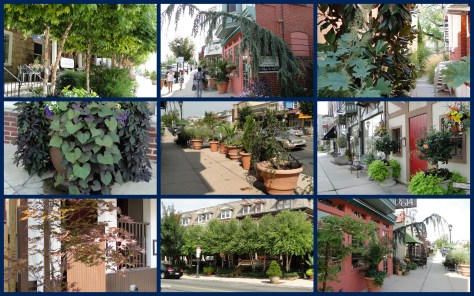

William Penn’s original square mile city, bounded by the four squares of Rittenhouse, Washington, Franklin and Logan, still retains an orderly grid. The absence of a glass and steel jungle blotting out the sun, and the presence of 300 year old alleyways lined with colonial houses allows Philadelphia to feel like a home for humans, rather than just an economic engine. Visionary city planners as early as the late 1700’s designed the grand boulevard, the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, that stretches from City Hall/Logan Circle to the Art Museum. It’s hard to experience a finer entrance to a city than the tree-lined, flag bedecked, fountain anchored Parkway. Its space, like a giant front lawn, is shared by commuters, strollers, special events, runners, frisby players, three generations of Calder family sculptures and many cultural institutions. Yet one square mile Philadelphia was an urban economic engine in the 18th and 19th centuries with all the accompanying issues of pollution, muddy streets, poor sanitation and summer “fever” epidemics.

The 1920’s Greek temple that is the Philadelphia Museum of Art stands, appropriately, on a hill at the far end of the Parkway. Its galleries contain priceless collections spanning millennia. Music and social events are not new to museums, but Art After 5 (every Friday from 5:00 to 8:00) has become a fixture in Philadelphia’s “TGIF” venues. There are a limited number of tables that fill quickly but sitting on the smooth marble of the grand staircase, under the gaze of an enormous backlit “Diana,” creates an amphitheater feel. The central hall rises up one floor to a broad mezzanine where it’s possible to sit as well. Two full service bars and a professional, personable wait staff serve light fare and drinks. It’s an informal, club atmosphere and people wander through the adjoining galleries while the music filters in as doors open adding to the visual experience.

From the gazebos that sits on a rocky promontory outside the museum there’s a nice view of the Waterworks and Boathouse Row.

An engineering marvel when it opened in the early 19th century, the municipal Waterworks pumped fresh Schuylkill River water directly into an ever-expanding city. Today its restored buildings house a pricey restaurant, small museum and provide public space as part of Fairmount Park. Boathouse Row stretches just beyond. This collection of late 19th century stone and wooden houses represent generations of private university associated sculling clubs. Although the sport is often thought of in the same league as polo, dressage and fox-hunting, the skill necessary to compete in sculling is achieved only after arduous physical training. In Philadelphia, it’s a serious sport.

The 1740 Livezey House has that stately look of so many of the well-preserved antique houses in Valley Green and the neighborhood of Chestnut Hill. From the Art Museum it’s possible to hike or bike the five miles on trails that meander through the thickly forested Park, along the river and creek, directly to Valley Green and Chestnut Hill. Yet except for the pre-1870 houses, little of this countryside was bucolic as late as the 1870’s. The banks of the Schuylkill River and Wissahickon Creek had been denuded of trees for nearly 200 years and over built with a series of small company towns while its polluted waters were harnessed to provide energy for the mills that were part of Philadelphia’s economic engine. Mr. Thomas Livezey made a nice fortune from his Wissahickon Creek mill but his surroundings were certainly not as attractive as today.

It was the threat to Philadelphia’s drinking water that spurred the building of the long-planned 9,000 acre Fairmount city park. Its serpentine shape deliberately included both the Schuylkill River and Wissahickon Creek within its boundaries. Gone were dozens of Colonial and early 19th century mills, houses and entire small company towns. The Park-owned historic Rittenhouse Town is an exception and provides a glimpse of life when it was a company town/suburb to Philadelphia’s one square mile city. Yet since the town’s business was paper making one can be sure few trees existed when it was purchased by the Park Commission in the 1870’s. Restoration of the watershed, over a century later, is still ongoing. These generally affluent neighborhoods today have the look and feel of story book versions of leafy, bucolic Colonial villages, and yet they’re within the bounds of a 21st century city.

The Valley Green Inn on Forbidden Drive (cars were banned in 1920) has been open since 1850 but with a checkered history. In the past few years it seems to have secured its future as a venue for fine interpretations of classic American and Continental fare. It’s setting directly on the Wissahickon Creek with its antique decorated dining rooms make it an ideal venue for any occasion. There’s nothing better than taking a walk along the 7-mile Forbidden Drive after lunch nearly any time of the year, and if you’re riding your horse, you can still hitch it to the posts outside the Inn.

You must be logged in to post a comment.